Through the arthroscope, the anatomy has to be interpreted from the restricted circular front view one gains via the camera.

First published by knee surgeon Angus Strover in 2008, and reviewed August 2023 by Dr Sheila Strover (Clinical Editor)

First published by knee surgeon Angus Strover in 2008, and reviewed August 2023 by Dr Sheila Strover (Clinical Editor)

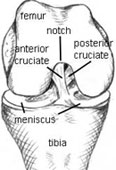

The inside of the knee joint is dominated by the two femoral condyles, the shiny rounded ends of the femur bone (thighbone).

If you imagine that the arthroscope has been inserted into the antero-lateral portal, it will shine initially into the gap between the two condyles. This area is called the 'intercondylar notch'because it intervenes between the two femoral condyles . The notch houses the very important cruciate ligaments. Let's look at this anatomy in a bit more depth.

The lower end of the femur, including the rounded femoral condyles, is covered with shiny white gristle, called hyaline cartilage or articular cartilage. The full extent of this cartilage is only evident when the knee is bent, although in the image above the artist has taken a bit of artistic liberty showing it in a straightened knee. During flexion and extension of the knee (bending and straightening) the condyles are rolled over the flattened tibial plateau, at the top of the tibia. Integrity of the hyaline cartilage is critical for the smooth functioning of the knee, and damaged cartilage gives rise to pain and subsequent arthritis.

Between the two bones, acting as space fillers and shock absorbers are the flattish wedge-shaped menisci (semilunar cartilages), looking rather like flattened orange segments. Composed of a tough spongy material, they are also critical to smooth joint functioning, cushioning the irregular space between the rounded condyles of the femur and the flattened tibial plateau.

I'm going to go into the anatomy in more detail, but before I do I want to mention something about terminology.

The menisci, the wedge-shaped shock absorbers of the knee, are shaped like a half-moon. For this reason they used to be called 'semi-lunar' cartilages. But confusion arose because doctors also used this word 'cartilage' to mean the white joint covering (gristle) at the ends of bones. So doctors dropped 'semi-lunar cartilages' and called the shock absorbers 'menisci'.

That seems straight-forward, but unfortunately the confusion didn't go away, as patients got used to talking about 'the cartilages' when they were meaning the shock-absorbers.

So if I am talking about the shock absorbers, I will call them 'menisci' - OK?

Menisci

Here is a photo of a real set of menisci taken from a cadaver for use in a meniscal transpant operation. What do you think that fleshy stuff is in the middle between the two menisci? Yes - the cruciate ligaments. They have been cut off to free the graft from the femur.

The meniscus on the outer aspect of the knee is the lateral meniscus, and that on the inner side is the medial meniscus. The inner edge is flattened, while the outer edge is thicker. At the front (anterior) and back (posterior) the pointed ends are called the 'horns' of the meniscus. Hence each meniscus has an anterior horn and a posterior horn - and both can be difficult to reach during arthroscopy.

You will see that the two menisci are a bit different in shape. The medial meniscus is more 'C-shaped' while the lateral meniscus is more 'O-shaped'. The C-shaped medial meniscus is fixed to the joint capsule all around its edge, and there is very little mobility. The O-shaped lateral one, on the other hand is very mobile.

Which one do you think is more prone to tear? Yes, the medial meniscus. Because it cannot move much, a shearing force may tear it as it cannot absorb this strain.

Cruciate Ligaments

The cruciate ligaments connect tibia to femur in the middle of the joint space. The word 'cruciate' means 'crossed' - and the two ligaments cross over one another. They are very important for the stability of the knee. The mechanism by which the cruciates maintain optimal stability is beyond the scope of this course. For our purposes I just want to point out a few key features when it comes to assessing their integrity:

- they actually lie outside the joint cavity, and what you can see from the inside is the shiny joint lining covering them

- this covering may confuse the amateur, as it may give the appearance of the cruciates being intact, when in fact they may be completely ruptured. Or they may have pulled off from their bony attachment.

Collateral Ligaments

Those of you with collateral ligament injuries may be wondering why I have not shown the collateral ligaments. Actually, the collateral ligaments cannot be seen from within the joint, as they are outside the waterproof capsule of the joint.

On the other hand, the undersurface of the patella bone (kneecap) CAN be seen from within the joint, but the position of the arthroscope has to be changed to view this properly. In the big image above if has been peeled to one side to show you what it looks like, but we will be getting back to this later.

Patella

Now I am going to go back to the bones and talk a bit about the patella - the kneecap.

Here is an MRI scan, looking at the knee bones from the side, and where contrast has been reversed so that the bones are dark. You can recognise the rounded ends of the femur and the flattened top of the tibia.

The patella (red arrow) is quite peculiar. It is located right in the middle of the tendon of the quadriceps muscle, the muscle which forms most of your 'lap'- the tendon being the bit at the lower end where the muscle attaches to the tibia. From inside the joint only the undersurface of the patella is visible. The tendon above and below lies ouside the joint lining and cannot be seen.

The arrow shows you the undersurface of the patella. You can see how it only its undersurface projects into the joint cavity (white). Any idea what that triangular grey mass is which is projecting into the knee joint below the patella?

Did you get it? If so, well done. It is the fat pad.

Fat Pad

The fat pad can be the bane of an arthroscopist's life, as it is bright yellow in colour and can often cover the end of the arthroscope and obscure the view.

Some years ago, a knee surgeon would have thought little about cutting away the offending bit, but now it is recognised, not only that it plays an important protective role, but also that scarring can be crippling to the patient.

Synovium

Well, we have walked around most of the structures in the knee cavity now, but we have not talked much about the cavity itself and the important joint lining, or synovium. The synovium is a glistening membrane which lines the walls of the cavity, and which secretes 'synovial fluid' to luricate the inside of the joint.

From the point of view of arthroscopy, it is important to know that the joint cavity extends upwards, a handsbreadth above the patella, into a pocket called the 'suprapatellar pouch' - literally 'the pouch above the patella'. You can see this pocket in these MRI scans (white colour in this view). Surgeons often fail to fully examine this area, particularly with the arthroscope above the patella, and problems can be missed.

Actually, on either side of the tibia, too, there are similar depressions called the 'parapatellar gutters' - literally 'the gutters alongside the patella'. Although these are not so deep as the suprapatellar pouch, they are important because gravity may allow lttle bits of material to slip down and hide there, most often 'loose bodies'.

Loose bodies are bits of joint cartilage which have broken off into the joint, but which can then be nourished by it and grow quite big. Periodically they cause nasty symptoms by getting caught between the bones, but when the surgeon looks for them they may slip quietly into the parapatellar gutters to the sides and back - and need to be looked for.

Similarly, at the back of the knee behind the cruciates loose bodies may lurk in a fold of synovium and be hard to detect.

Synovial Plicae

A plica is a fold of synovium inside the knee cavity, stretching across the joint. They may exist normally in three anatomical places:

- above the patella (SPP=suprapatellar plica)

- along the rounded edge of the femur, to the side of the patella (MPP=medial patellar plica)

- in the notch of the femur below the patella (IPP=ifrapatellar plica)

When plicae are soft and stretchy they cause little trouble in the knee. But little episodes of direct trauma (bangs and bumps) may cause them to become inflamed, to thicken up with scar tissue and interfere with the smooth working of the joint. We'll look at them again later in the course.