When it comes to meniscal tears what we as surgeons are interested in are –

This depends partly on the complexity of the tear (including its shape) and the zone of the meniscus involved.

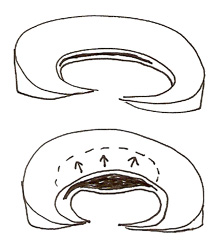

The femur (thigh bone) is round and the tibia (shin bone) is flat. Without the menisci you have round bone meeting flat bone. To accommodate the roundness of the end of the femur are these C-shaped meniscal shock absorbers – on the inside the medial, and on the outside the lateral. They take the force and dissipate it, and are very clever in the way that they are designed with the fibres running in very specific directions to provide so-called ‘hoop stresses’ or strength in the meniscus.

They are always compared to the hoops around a wooden wine barrel – because of the arrangement of those hoops the barrel is extremely strong, but the minute you take one of those hoops away it becomes weak. So if the meniscus is damaged and torn in a longitudinal fashion it follows the hoops, and it is not nearly as bad as if you tear it in a radial fashion when you tear across those hoops and completely de-function the meniscus. Besides acting as a shock absorber, the meniscus also provides a little bit of lubrication to the knee joint.

Complexity of the meniscal tear

With the meniscal tears that we see, we tend to divide them into simple and complex. So simple means that it is torn in just one plane and complex means that it is torn in more than one plane.

- longitudinal (a long split running from the front of the meniscus to the back)

- horizontal (or horizontal cleavage)

- radial (where it splits in a radial direction). They are almost the worst tears to get because they are very difficult to repair, and when you come to debride (trim) them you need to debride a lot of tissue

- flaps (where some pieces break off to create flaps).

With longitudinal tears going right through from top to bottom, if the split extends far enough it can flip in such a way that inner part creates a handle a bit like a bucket handle – we call it a bucket-handle tear and it is a very classic type of tear. There are different types of small flap tear that have characteristic shapes – the most common is called the parrot beak tear.

Meniscal blood supply

So to summarise, in adults with a longitudinal tear, management will depend on where the tear occurs – those in the white-white zone get excised, those in the red-red and red-white zones one can repair, but a red-red repair is likely to give the best results.

Complex tears, for example longitudinal with a flap or longitudinal with a radial component, are essentially non-reparable.

So when a patient has a meniscal tear a surgeon wants to determine “what shape is the tear and where about is it occurring?”, one can tell a great deal from the MRI scan, which will tell if the tear is longitudinal (like in the MRI scan on the right - circled in yellow), radial or a horizontal cleavage, and one can see from where the tear is on the MRI scan how peripheral it is and therefore how likely it is that it will be reparable. The other thing of course is the history (the patient’s story).

There are two main ways in which this will present –

- a true traumatic event

These tears are usually more easy to repair. The patient has an injury, falls over and twists the knee – “ I was running, I stumbled on something and twisted my knee and have had pain on the inner side of my knee ever since. It swelled the next day. It is not really settling”. The pain is worse with activities, particularly impact activities, but it is also present to a degree when resting and at night (patients often say they sleep with a pillow between their legs to keep the knees from knocking together because it is so tender to touch over the area where the meniscus has been torn). On examining there is reduced range of motion and that delayed sort of swelling which they get. There is very localised pin-point tenderness and localised pain, usually over the medial joint line (particularly posteriorly) because the medial meniscus (and particularly the postero-medial meniscus) gets torn a lot more commonly than the lateral meniscus. Often patients struggle to get full extension - if one asks the patient while standing to push their knee back to get hyper-straight, they will find that very uncomfortable although they can usually do it. This is in contrast to the relatively unusual situation where a longitudinal extends (usually traumatically) and the handle flips into the middle of the knee and properly prevents the patient from fully extending the knee (‘locked knee’).

We also have a series of provocative tests that we can do – like Thessaly’s test or duck walking (walking in a half squat) that provoke particular irritation of the tear, but to be honest one can pretty much predict from the history and the clinical examination whether someone does indeed have a meniscal tear. - A degenerative tear with no real traumatic event

It is less likely that these tears are reparable. In this group there is no real history of trauma, but the knee hurts similarly usually on the medial side – “It’s just here, doctor, right on the back corner”. When one examines them, there is a usually a small effusion (fluid in the joint), and the patient is very tender over where the meniscus is torn.

So one gets a lot from the history, the examination and the MRI. There are certain other tests that we can do to home in on whether or not the meniscus is torn, but it is usually quite an easy diagnosis to make. Then it boils down to the shape of the tear and the location of the tear, and one is also influenced to an extent by the patient’s age. Another factor is chronicity (how long since the injury)– it is amazing how some doctors pull figures out of the hat, saying that they will not repair a tear if it is more than say six weeks old, preferring instead to excise it . I believe that if shape and location are favourable and the tissue is in good condition then one ought to try a repair.

Medial or lateral?

The larger medial meniscus is firmly fixed to the top of the tibia and does not really move very much. In comparison, the smaller lateral meniscus is hyper-mobile - when you bend your knee the lateral meniscus actually travels off the back of the tibia. If you do an MRI scan using a dynamic MRI, when the knee is fully bent you can actually see the whole of the lateral meniscus shifted off the back of the tibia out of harm’s way, whereas on the medial side it stays put. There is a lot more force going through the medial meniscus when you bend your knee than there is going through the lateral meniscus. Also most of us are aligned such that our weight-bearing line tends to go more through the medial side of the knee. The combination of these factors means that there are many more injuries to the medial meniscus than to the lateral meniscus.

Take the typical sort of 50 year old patient who bends to pick something up or has a very minor innocuous injury to the knee and has suddenly got this problem of pain, swelling and localised tenderness – it is much more common for that to occur on the medial side than on the lateral side.

That is the bad news – the good news is that an injury to the medial meniscus is much less significant than an injury to the lateral meniscus. The lateral meniscus is a much more important structure in terms of maintaining function.

We divide the meniscus into thirds from front to back – the front third is the anterior third, then there is the middle third, and then at the back is the posterior third. Classically most meniscal tears occur in the posterior third because that is where the highest load is going through the meniscus at any one time. During repeated bent knee activity – climbing stairs, particularly coming down stairs, bending the knee beyond 90 degrees – the highest forces are going through the back of the knee and that is where the meniscus tends to split. Patients avoid bending and squatting, have difficulty getting into and out of the bath, they avoid impact, and they avoid running, they definitely avoid twisting.

Repeatedly I hear patients ask “Why has this happened to me?”, and my answer is that from the age of about 30 onwards the water content of the meniscus drops off quite significantly and the meniscus starts to become less mobile, less forgiving and more brittle. The older you get the more brittle it becomes. That is why you can be 40 year of age and then for no good reason you present with this painful, swollen knee with localised tenderness.

Such a tear can either be traumatic or degenerative. It is more common to have longitudinal and radial tears with trauma, while the horizontal cleavage tear tends to be a more common degenerative wear-and-tear phenomenon. However, all the shapes and situations of tear are possible – so you can get an 18 year old boy and he may have a flap tear with a loose parrot- beak bit of meniscus torn away through some minor injury on a sporting field or you can scope a 65 year old’s knee and see exactly the same thing. There is usually at least some degree of trauma, either innocuous or something more significant where the knee is twisted awkwardly. With significant trauma there is often associated damage – for instance, 60% of those individuals that tear their anterior cruciate ligament will also have will also have a medial and/or lateral meniscal tear. If you look close enough, nearly everyone that has an ACL (anterior cruciate ligament) rupture has a very small tear of the posterior horn of the lateral meniscus because of the way the knee twisted at the time of the injury.

Deciding on surgery

There are a significant number of patients who have minor injuries and have some form of meniscal damage but get over it – these would be stable tears. The patients that need surgery are the ones that present with ongoing pain, instability, loss of movement, swelling and the symptoms I have described, like pain at night. Most meniscal tears that are bad enough for a patient to present to their general practitioner (family doctor) or A&E (emergency department) don’t settle, or they certainly don’t settle quickly. What is very classic is for the patient to say “The thing I cannot understand is that I have good days and I have bad days. Some days I can do anything I like, and at other times I cannot do anything as it is so painful!”. Well, what happens is that the meniscal tissue, the flap, will invariably sit in a reasonable position much of the time. The analogy I use with my patients is that it is like a torn carpet by a door – if the carpet tear gets ruffled up the door won’t open and close. Then someone comes into the room and the carpet gets put back into a nice flat orientation and it is no longer a problem with the door until someone ruffles up that torn bit again.

Most of these patients are at least six or eight weeks down the line. Most people are sensible enough not to run straight to their doctor and have a trial of anti-inflammatories and physiotherapy and see if things settle. But after a couple of months they have put up with their pain for long enough, and come in to see us when we tend to order an MRI and can show the patient what the problem is.

- Complex

Generally speaking the complex tears are not reparable and the aim of any treatment is surgical debridement – tidying them up, effectively. - Simple

Simple tears can be classified in a number of different ways – orthopaedic surgeons love to classify things! We classify them partly on what shape they are.