Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) tears are a problem. There are approximately 100,000 ACL tears in the USA each year at a financial cost of $1.7 billion.

Most injuries are sport specific, however, non-contact ACL injuries seem to follow a more gender-specific trend. Female athletes sustain ACL injuries 2 to 8 times more frequently than male athletes!

The high risk group for these ACL injuries is females between the ages of 14 and 20 years and 70% of ACL injuries occur in non-contact situations. The sports where the incidence of ACL injuries is the highest are sports such as soccer, volleyball and basketball that require pivoting, cutting and rapid deceleration.

In 1972 a USA amendment, Title IX, was passed that enabled women to participate in athletic events without gender or financial discrimination. This legislation not only resulted in a 6-fold increase in female sports participation to over 3 million in 2004 with soccer the number 1 female sport at collegiate level, but it also resulted in a large increase in the number of sport related injury, including non-contact ACL injuries.

With this dramatic increase in ACL injury the sports medicine community wanted to determine why females are more prone to ACL injuries than their male counterparts. Studies looked at a variety of aspects to try to identify the main factors that lead to an increased risk of ACL injury in females. The four areas that have been associated with increased risk of ACL injury in the female athlete are anatomy, hormones, environment and biomechanics. The size and shape of the ACL, the intercondylar notch and the pelvis; ligament laxity; body mass index (BMI); and hormonal variations have all been evaluated as potential factors for ACL injury. Despite some excellent studies looking at risk factors for ACL injury no single environmental, anatomic or hormonal factor has been shown to be responsible for the increased risk of ACL injury in female athletes.

Research efforts have now switched to looking at whether biomechanical and neuromuscular factors directly contribute to ACL tears. Women typically run more erect than men and have decreased knee and hip flexion. In addition, women activate their hamstring muscles more slowly than males when decelerating. This is very important when the role of the ACL is considered. The ACL is important in stabilizing the knee joint by preventing forward movement of the tibia (shin bone) in relation to the femur (thigh bone). The combination of decreased knee flexion and slower hamstring activation result in the ACL being put under increased stress in females compared to males especially when landing from a jump or decelerating.

What is the PEP Program?

The PEP Program is a highly specific 20-minute training session that replaces the traditional warm-up. It was developed by a team of physicians, physical therapists, athletic trainers and coaches in California. The program's main focus is educating players on strategies to avoid injury and includes specific exercises targeting problems as identified in previous research studies.

The athletes perform the PEP program 2 to 3 times a week. The 20 minute program is performed on the field and doesn't need any specialist equipment. Full details of the PEP program can be found online at www.aclprevent.com.

The emphasis of the program is on proper landing technique and stresses 'soft' landing with deep hip and knee flexion as opposed to landing with a 'flat foot'. The athletes are shown a deceleration technique called the '3-step-stop' that spreads the forces that occur at the knee on deceleration over 3 steps instead of 1, thus reducing the stress on the ACL.

Results of Our Study

Our research group collected data for two years on the incidence of knee injuries in female soccer players in the USA Coast Soccer League. A total of 52 teams and 1041 female soccer players between the ages of 14 and 18 years were enrolled into the PEP program and the players from the remaining 112 teams and 1091 players acted as a control group to compare the PEP program group against. Throughout the 2000 and 2001 seasons every week coaches for each of the teams would report injuries and if the injury was a knee injury the player was given a knee injury questionnaire to complete.

We thought that a neuromuscular training program, such as PEP, would have a beneficial effect on ACL injuries but we didn't realize that our results would yield quite such dramatic improvements. In the first year of introducing the PEP program there were 2 ACL tears in the 1041 athletes who took part in the PEP program compared to 32 ACL tears in the control group of 1091. That means that for the first year of the program we had an 88% reduction in ACL tears for the season in the PEP athletes. In the second year there were 4 ACL tears in the PEP group (844 athletes) compared to 35 ACL tears (1913) in the control group. This resulted in an overall 74% reduction in ACL tears.

One of the limitations of our study was the fact that all the teams in the PEP group enrolled voluntarily and weren't selected at random. However, we felt that due to the large number of athletes who took part in the study the effect that this non-randomization had on our results was minimal.

We completed a second study in the collegiate population (ages 18 to 22) in sixty-one NCAA Division I Women's soccer programs in the fall, 2002 season. Our results were of equal success. Throughout the fall season, there was a 72% overall decrease in non-contact ACL injuries compared to the control group. When the data was stratified with respect to time, there was a 100% decrease in contact and non-contact ACL injury during games and practice sessions in the last six weeks of the season. In addition, we looked at those athletes that had previously sustained an ACL injury and have since successfully returned to play. In this population, we had an 80% decrease in the recurrence of contact ACL injury and a 100% decrease in the recurrence of non-contact ACL injury. This study was a randomized controlled trial, thus no motivational or selection bias affected the results.

In our studies we demonstrated that the PEP program did significantly reduce ACL tears in both our 14-18 year old and 18-22 year old female soccer players but what we wanted to know then was how it helped to prevent ACL injuries.

Biomechanical Analysis

What we wanted to do was to assess the actual impact the PEP program had on forces that were going through the knee so we biomechanically analysed a player before and after the program. Female athletes were analysed using 3-dimensional video and instruments that can measure forces whilst they performed a sports specific manoeuver.

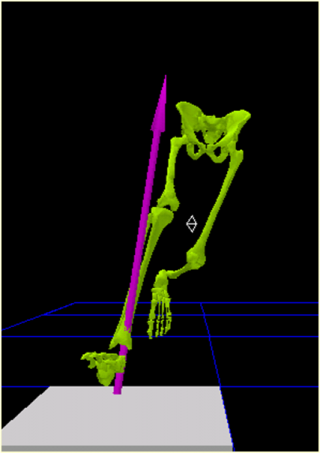

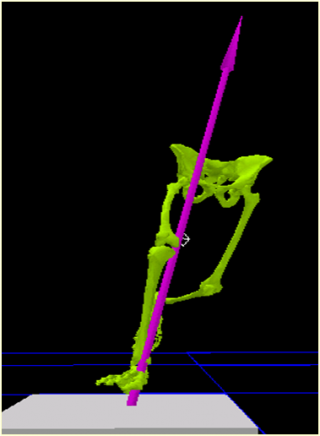

The arrow in the images below shows the ground reaction force (GRF). The GRF is the force that is created when the foot makes contact with the ground and the direction and size of the force can be accurately measured.

This image shows the ground reaction force (line with arrow) before the athlete performed the PEP program.

This image shows the ground reaction force (line with arrow) after the athlete performed the PEP program for twelve weeks.

You can see that before the PEP program in this individual during a cutting maneuver the line ran on the outerside of the knee joint and totally outside of the hip and pelvis. After performing the PEP program for twelve weeks the athlete performing the same cutting maneuver resulted in the line shifting to the innerside of the knee joint and through the pelvis. This is very relevant as we think that the more the ground reaction force runs on the outside of the limb, the greater the propensity for the knee to move into an inward or caved in position. This is a dangerous position for the knee - as it results in direct tension to the MCL and ACL ligaments, respectively.

Future Directions

On the basis of the success of our PEP program in soccer we are now looking at another high risk sport for ACL injury - women's basketball. A randomized controlled trial is being planned and we have already implemented a pilot program similar to the soccer program and have had 0 ACL injuries and a 62% decrease in hip, low back, knee and ankle injuries.

The PEP program comprises a number of different exercises that work on different but complimentary aspects. We know that the PEP program works in reducing ACL injuries and we know that it can alter the line of the ground reaction force but what we need to look at now is whether we can identify which of the components of the PEP program are the most important in determining this decrease in the rate of non contact ACL injuries.

References

On-line details of the ACL Prevention Program:

Santa Monica ACL Prevention Project

PEP program - web-based lesson for athletes, coaches, trainers and parents