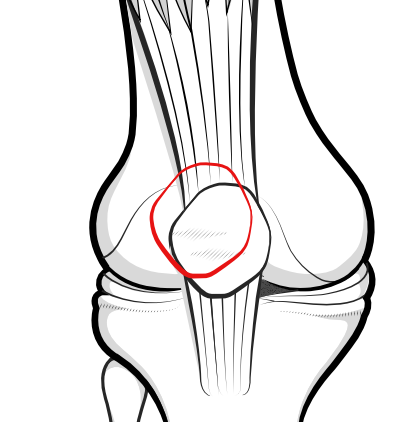

Patellar instability is the uncomfortable condition where the kneecap is not always properly contained within the walls of the underlying groove of the femur.

Patellofemoral congruity

In the normal situation, the patella is contained within the underlying groove of the femur during bending and straightening of the knee. Because the groove is shallower at the top end where the patella is in contact during extension, it follows that the patella is only shallowly engaged when the knee is straight. As the knee is bent, the patella is forced into the lower region of the groove, where it is deepest, so the patella is most deeply engaged when the knee is bent as in this illustration.

Sometimes the patella may not properly engage in the normal way. It may slip to the side, nearly breaching the wall of the groove - which is called patellar subluxation. Or it may jump right out of the groove and over the edge - which is called patellar dislocation. There are various grades of both subluxation and dislocation. Dislocation or subluxation occur more easily as the knee is extended.

Soft tissues holding the kneecap in place

Besides the walls of the trochlear groove, several other structures are important in keeping the kneecap from jumping out. These include:

strong quadriceps muscles, and intact quadriceps and patellar tendons

The patella is an unusual bone as it is contained within the tendon of the quadriceps muscle. The part above the patella is called the quadriceps tendon and the part below is called the patellar tendon. A weak quadriceps muscle may make it easier for the patella to pop out of place.

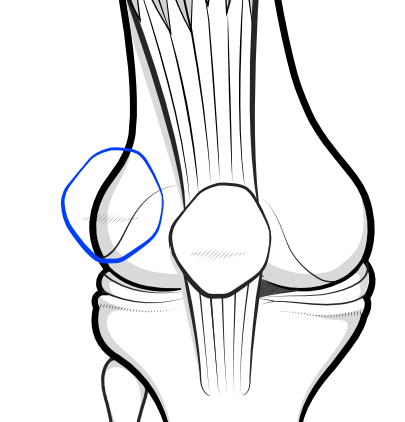

a correctly-tensioned lateral retinaculum

The medial and lateral retinaculum are sheets of fibrous material on the outer side of the kneecap (patella) that help to support the patella in a central position. This sheet of tissue may become tight if the forces around the kneecap are not in balance. The medial retinaculum is also important but less inclined to cause a problem.

A tight lateral retinaculum may be associated with patellar tilt which can itself result in excessive lateral pressure syndrome (or hyperpressure syndrome) with increased pressure on both the edge of the patella and the wall of the trochlear, associated with pain in the front of the knee, but this is not the same thing as patellar instability.

an intact medial patellofemoral ligament

The medial patellofemoral ligament (MPFL) is the main medial soft tissue stabiliser of the patella. It is a band of retinacular tissue on the medial side of the knee which is called into play particularly as the knee starts to bend. After a first patellar dislocation event the MPFL can stretch or rupture, making it easier for subsequent dislocations to occur.

a correctly positioned tibial tubercle

The patellar tendon attaches the whole extensor mechanism - that is, quads muscle, quads tendon, patella, patellar tendon - to the tibia bone at the eminence called the tibial tubercle. The tibial tubercle is normally in a position in good alignment with the rest of the extensor mechanism, and if it abnormally positioned out to the outer side, this puts a lateral drag on the tendon and patella. The alignment can be measured using a calculation called the tt-tg distance.

Patellar subluxation

Subluxation means that the kneecap almost dislocates - i.e. slips up the side of the underlying groove of the femur bone - but does not quite slip over it.

The term 'subluxation' is actually used a little loosely:

- a surgeon may indicate 'subluxation' on an x-ray, when indicating that part of the patella habitually rides outside the underlying rim of the trochlear groove, but the patient may not actually be experiencing any symptoms.

- a surgeon may ask you if you 'sublux', in this case meaning that you periodically feel the patella suddenly - and uncomfortably - jump partly over this rim. This is a discomfort, rather than something you can see. To elicit this the surgeon may perform a patellar apprehension test, trying to push the kneecap sideways out of the groove in an attempt to physically 'sublux' the patella. If the patient anxiously restrains the examiner from doing this, it is termed a positive apprehension test, and suggests that the patient has previously experienced pain from instability.

Kneecap dislocation

Kneecap dislocation is different from subluxation. Subluxation is more of a sensation for the patient, but in a dislocation the patient is likely to see a gross deformity of the patella, which may spontaneously reduce or which may remain in this very distressing position.

For this to happen it is likely that the MPFL ligament has stretched or torn, and there may also have been a flake of cartilage and bone knocked off (osteochondral fragment).

Such dislocation may be a once-only event, or it may become recurrent, habitual or permanent.

Primary traumatic patellar dislocation. Tsai C-H, Hsu C-J, Hung C-H and Hsu H-C. J Orthop Surg Res. 2012; 7: 21.

Congenital patellar instability

Patellar instability can be congenital or acquired. Congenital implies that the person was born with underlying structural or physiological problems that make it easier for the patella to slip out . Acquired implies that things were fine, but an injury or inappropriate surgery may have changed the normal structural balance, allowing subluxation or dislocation to occur.

Congenital conditions associated with patellar instability include:

Congenital hypermobility

Hypermobility is something one is born with, and is usually genetically inherited. The person with 'rubber joints' or 'double joints' usually does not need a doctor to tell them that their ligaments are lax, but it may take a while to determine which of the various hypermobililty syndromes (eg Ehlers Danlos Syndrome, Marfan syndrome) is causing the problem.

People born with generalised ligament laxity will likely be used to doing party tricks to amuse their friends, like bending their thumb to touch their forearm or bending their fingers backwards, but unfortunately excessive joint mobility is frequently associated with knee problems, and in particular recurrent dislocation of the patella.

Congenital Patella Alta

Patella alta is a condition where the kneecap is in a higher position than normal. In this position it may not readily engage in the groove of the underlying tibia in the first few degrees of bending, and may sublux or even dislocate. In patella alta the patellar tendon may be abnormally long or the tibial tubercle, to which the patellar tendon attaches, may be in an abnormally high position.

Congenital Patellofemoral Dysplasia

Dysplasia refers to a different problem - one in which the patella and/or its underlying groove is an abnormal shape - in which case the patella is not properly contained within the groove when the knee is bent and may dislocate. In patellar dysplasia the patella is an abnormal shape. In trochlear dysplasia the groove may be flattened or even heaped up into a bump.

Congenital valgus deformity

Valgus deformity, or knock-knees, can also predispose to patellar instability.

Acquired patellar instability

Acquired patellar instability is where patellar subluxation or dislocation is not due to a condition one is born with, but is due to a problem that occurred later. Causes of acquired patellar instability include:

Previous dislocation event

A previous traumatic dislocation event may have damaged the medial patellofemoral ligament (MPFL), which is one of the important constraints holding the patella in its normal alignment. This may be associated with a small osteochondral fracture of the at the edge of the patella or femoral groove with the defect compromising stability of the kneecap.

Inappropriate surgery

Inappropriate surgery, such as the performance of an overextensive lateral release or a lateral release for the wrong indications, may leave the patella vulnerable to subluxation and dislocation. The patella may even sublux or dislocate medially rather than laterally, and in bad cases it may jump out either way.

Muscle weakness

Weakness of the extensor muscles from disuse, such as after an injury or surgery, may leave the patella vulnerable to subluxation.

Patellar tilt, malalignment and maltracking - what's the difference?

Patellar tilt, malalignment and maltracking are words that describe how the patella relates to the groove of the femur bone with which it comes into contact as the knee bends.

Patellar tilt

In patellar tilt, the patella is situated in the middle of the groove in which it normally rides (the trochlear groove of the femur), but it is tilted over to one side because of tightness of the normal fibrous support there. The tilt is usually to the outer or lateral side.

Patellar malalignment

Malalignment means that the patella in not central in its underlying groove but is too far over either to the inner (medial) or outer (lateral side). The patella may be pulled over too far to the side (usually lateral) by any of several structures being poorly aligned. For example, if the attachment of the patellar tendon to the tibia bone is in a poor position this may cause the malalignment.

A patella may be both tilted and malaligned. This implies both a local cause (tight lateral retinaculum) associated with a more distant problem, such as a poorly-positioned tibial tubercle.

Patellar maltracking

Patellar maltracking means that the excursion of the patella as the knee bends and straightens is not central, but tends to one or other side. Clearly, the terms malalignment and maltracking are similar, but one really relates to a static position (eg as one might see on an X-ray or during surgery), while the other relates to the situation during movement of the knee.

Braces for kneecap instability

Patellar instability braces have a 'cut out', allowing an unstable patella to be supported. Patellar tendon braces alter the forces on the patellar tendon, and/or quads tendons.

Patellar instability braces are designed to push the patella towards the midline (medially), aligning the extensor mechanism optimally in the groove of the femur, but may also affect the joint by improving warmth, sensation and circulation.

They are generally made of a sleeve of soft material, such as Neoprene, and have a cutout for the patella. Most include some kind of buttress, usually on the lateral side, or a raised ring ('do-nut') protecting the whole patella.

They may be 'static' (the majority) where there is no actual force applied to the patella, or 'dynamic' (e.g. Palumbo), where elasticised arms provide both force and counterforce to the patella. Patellar tendon supports (e.g. Cho-Pat strap) may also be thought of as patellar braces.

Commercial Patellar Braces

- Palumbo patellar stabilising brace (Palumbo orthopaedics)

- Neoprene sports brace (Townsend design)

- Bledsoe sport Max (Bledsoe brace system)

- Patellar brace (Pro Orthopaedic Device Inc)

- Ortho-care body flex (Orthocare)

- Omni Scientific Sport sleeve (Omni Scientific)

- OnTrack (OrthoRx, Inc.)

- Knee Protec (Pro-tec)

- Cho-pat Strap (Cho-pat)

Surgical procedures to correct patellar alignment

Competent physiotherapy is usually the first line of management for patellar maltracking, and surgery should only be considered when this fails, then realignment surgery may be considered when it is important to improve kneecap stability.

Proximal realignment procedures

Lateral Release

The most common proximal realignment procedure in the past has been the lateral release (also called lateral retinacular release). The main indication for this procedure today is symptomatic tilt of the patella without subluxation or dislocation.

A lateral release is a surgical procedure where tight structures to the outer side of the kneecap (patella), when they are causing the patella to tilt abnormally, are cut to allow the kneecap to assume a better position. Lateral release done for the right indications and done in the correct way may offer patients a significant improvement in their symptoms, but this procedure is not appropriate in patients who have an anatomic propensity to sublux or dislocate. Done for the wrong reasons, the procedure can be the beginning of a nightmare scenario for the patient, the physiotherapist and the surgeon. Even when it is done for the correct reasons, the cut must not extend into the vastus lateralis muscle, or it will cause inhibition of this muscle and affect the stability of the patella.

Lateral patellar retinacular release: changes over the last ten years. da Fonseca LPRM, Kawatake EH and de Castro Pochini A. Rev Bras Ortop. 2017 Jun-Jul; 52(4): 442–449.

Complications in Brief: Arthroscopic Lateral Release. Elkousy H. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012 Oct; 470(10): 2949–2953.

Lateral retinacular lengthening

It is becoming recognised amongst knee surgeons that this procedure has been inappropriately used in the past, and lateral release for lateral patellar instability (when the kneecap dislocates to the outside of the knee) has often contributed to the patient suffering instead from medial patellar instability (when the kneecap dislocates to the inside of the knee). Fewer and fewer knee surgeons are using the procedure of lateral release and for fewer indications, and where indicated, the procedure of lateral retinacular lengthening is preferable.

Medial reefing

Medial reefing is a procedure to try and pull the kneecap towards the midline by tightening the structures on the inner side, rather than releasing the structures on the outer side (lateral release). It is often done in conjunction with a lateral release.

The procedure involves placing strong stitches through the inner structures and pulling them tight.

Medial plication

Similar to reefing, but involves taking 'tucks' through the inner structures, like dressmaker's pleats.

Galleazzi procedure (hamstrings tenodesis)

This procedure is nowadays seldom done. It involves taking one of the hamstrings tendons, the semitendinosis tendon, and attaching it to the patella to pull it medially (semitendinosus tenodesis).

Distal realignment procedures

If proximal realignment procedures such as lateral release and medial reefing fail to correct the alignment of the patella, the surgeon may progress to a distal realignment procedure. Distal realignment procedures improve the relationship of the patella to the underlying trochlear groove by altering the anatomy below the kneecap. The different procedures generally carry the names of the surgeons who first described and promoted them:

Hauser procedure

This procedure is no longer done but is included here as there are many patients still symptomatic who have this procedure in the past. In this procedure the tibial tubercle with attached patellar tendon is cut and moved medially (towards the inner aspect), but no attempt is made to move it anteriorly (further forward).

Results have shown that the Hauser operation was effective in preventing further dislocation but did not prevent the development of osteoarthritis. Also, genu recurvatum (knees that can over-straighten) has been shown to be a consequence in young people when the operation was done before the growth plate in the tibia bone had closed.

Roux-Goldthwait procedure

In this procedure, the patellar tendon is split vertically. The outer (lateral) half is pulled through under the inner (medial) half and attached to the tibia, pulling the patella over to the medial side.

Maquet procedure

Maquet was the first to suggest that cutting the bone (tibial tubercle) to which the lower patellar (kneecap) tendon is attached, and bringing the kneecap forward would reduce the resultant backwards force described at the beginning of this page. He calculated that bringing the tibial tubercle forwards by two centimetres would reduce the backwards force by 50%. Some surgeons move it only one centimetre because they think that most of the effect comes in the first centimetre, and also the resultant deformity of the tubercle does not look so bad.

The Maquet operation requires a long cut alongside the kneecap and its tendon, and careful dissection of the kneecap tendon away from its underlying bone along its length. With a hammer and chisel the bone is cut, keeping the patellar tendon attachment intact and not breaking the bone piece free at the bottom end. The loosened piece of bone is then wedged forwards with a bone block, to elevate the tubercle by 1-2 cms. This bone block can be freeze-dried cadaveric (donor) bone, or can come from the patient's own hip (the top rim where you put your hands on your hips). Freeze dried is good as it does not compact as much as fresh bone.

Criticism of the Maquet is that the tubercle and tendon cannot easily be moved medially (towards the inner aspect of the knee) - maybe half a cm is possible, but not more. But there is no need for screws, and the patient is encouraged to mobilise early - CPM (continuous passive motion - on a CPM machine) and weight bearing (in an immobiliser) is begun immediately with weight bearing at 3-4 weeks post op.

Fulkerson Procedure

The Fulkerson procedure differs a bit from the Maquet. Here the bone is actually 'splintered' ('greensticked') at the lower end, allowing for more medial displacement(the bit of bone and tendon are moved more towards the inner aspect of the knee) and screws are used to hold the bits in place.

Elmslie-Trillat Procedure

This procedure is similar, but involves hinging the tibial tuberosity over medially.

Ligament Reconstruction versus Distal Realignment for Patellar Dislocation. Sillanpää P, Mattila VM, Visuri T, Mäenpää H and Pihlajamäki H. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008 Jun; 466(6): 1475–1484.

Other important procedures

MPFL reconstruction

Reconstruction of the medial patellofemoral ligament would be considered a reconstructive procedure rather than a realignment It involves using a graft to reconstruct a previously torn medial patellofemoral ligament.

Guidelines for medial patellofemoral ligament reconstruction in chronic lateral patellar instability. Sanchis-Alfonso V. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2014 Mar;22(3):175-82. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-22-03-175.

Simultaneous Medial and Lateral Patellofemoral Ligament Reconstruction for Combined Medial and Lateral Patellar Subluxation. Saper MG and Shneider DA. Arthrosc Tech. 2014 Apr; 3(2): e227–e231.

Trochleoplasty

Trochleoplasty is a constructive procedure, rather than a realignment, and involves re-shaping the groove of the trochlea. There are various methods for this, both via open surgery and keyhole surgery. If the issue is a 'bump' at the upper end of the trochlea, this too can be re-shaped. The new technique of arthroscopic trochleoplasty offers a minimally invasive solution to this challenging problem.

Distal femoral osteotomy

In cases of valgus deformity associated with patellar instability, a distal femoral osteotomy may be performed.

Medial Closing-Wedge Distal Femoral Osteotomy with Medial Patellofemoral Ligament Imbrication for Genu Valgum with Lateral Patellar Instability Sabbag OD, Woodmass JM, Wu IT, Krych AJ and Stuart MJ. Arthrosc Tech. 2017 Dec; 6(6): e2085–e2091.

Derotation osteotomy

This procedure is mentioned here for completeness. This procedure is rarely performed, and only in those rare cases where the tibial tubercle is in a bad position and the patient dislocates or subluxes because of the tibia bone (or even the femur) being rotated.

In this procedure the bone is cut through and rotated, and fixed into a new position, in order to properly realign the tibial tubercle.

Success of torsional correction surgery after failed surgeries for patellofemoral pain and instability Stevens PM, Gililland JM, Anderson LA, Mickelson JB, Nielson J and Klatt JW. Strategies Trauma Limb Reconstr. 2014 Apr; 9(1): 5–12.

Patellectomy

In very chronic cases of patellar instability where all else has failed, the surgeon may consider removing the patellar altogether.

PREVIOUS PART: Pain syndromes related to the patella

NEXT PART: Cartilage damage of the patella