A joint replacement is often a consideration when a patient is over 65 has developed painful and limiting knee arthritis.

What exactly does a joint replacement replace?

When we talk of a joint, we mean the region where two bones articulate, or move in relation to one another. The movement is made smooth because the bones are covered with the white “Teflon-like coating” called articular cartilage. When a total joint replacement is considered, it is usually because of irreparable damage to the majority of this articular cartilage. The underlying bone is generally also affected with fluid pockets (cysts) or bone swelling known as oedema. The regions inside the bone and on the edges on the outside of the bone where cartilage is lost can show cysts and bone spurs. This is the body’s clumsy attempt to fix itself.

However, there are other choices when considering a joint replacement procedure.

Total knee replacement

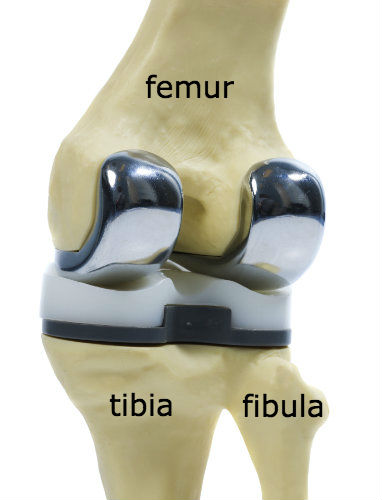

In a total knee replacement (or arthroplasty), the idea is generally to remove the joint cartilage and the underlying bone from the two sides of the knee in a block - one block from the femur bone and the other block - including both the medial and lateral menisci - from the tibia bone. After trimming off any interfering bone spurs, the removed areas are then replaced with precisely-fitting metal and plastic implants. The angles need to be correct, and jigs are used to determine what is cut away, while some surgeons use computer applications and imaging to determine where the cuts are made. Depending upon the design of the implant, one or both cruciate ligaments may also be removed.

You can see that this is quite a destructive process.

Partial knee replacement

A partial knee replacement - also called a unicompartmental knee replacement - is a much less destructive procedure, and is reserved for people where the arthritis only affects one side of the joint; in most cases that is the medial or internal half of your knee. It is essentially half of a total joint replacement. The advantages are that usually the lateral or external half of the knee, along with the kneecap and groove, the lateral meniscus and both cruciate ligaments are left intact. A partial knee replacement allows patients to be more active and the knee feels more normal than a total replacement.

|

|

|

Surface Replacement

The term 'resurfacing' is often used to refer to these types of smaller implants because they only replace the damaged area of joint cartilage. It does not involve the removal of a bone block as in the total or partial knee replacement; instead the damaged cartilage is removed and a shallow bone bed is created to place the implant into the surface. In knee surgery these implants are usually used on the surface of the condyles (end of the femur) or for the damaged kneecap and groove in which the kneecap (patella) runs. Because only the surface of the joint is replaced the rest of the structures in the knee, namely the menisci and cruciate ligaments are left intact. This allows patients to resume normal activity levels and even return to sports after the appropriate rehabilitation has been completed. This image shows a model of the knee, with the patella and its tendon pulled over the side to show where a metal trochlear (groove) implant has been positioned with its stem and the rear of the implant fixed in place with a special cement. A matching polyethylene (medical plastic) implant would similarly be placed at the back of the patella.

Such resurfacing procedures are helpful in the younger and active patient who has perhaps had a sporting injury to the knee that has damaged the joint surfaces of the kneecap and groove but where the articulation between tibia and femur is still good and all the knee ligaments are intact. Surface replacements can later be converted to a total joint replacement as the majority of the bone is left intact.

Biologics

There are also some conditions where there is aggressive focal destruction of joint cartilage - such as osteochondritis dissecans (when a chunk of bone and cartilage dislodges from the knee surface) and osteonecrosis also known as avascular necrosis. This latter is when the bone dies underneath the cartilage, eventually creating a cavity in the surface. While biologic treatments are usually the first choice in dealing with early cartilage damage, there are contra-indications and considerations to bear in mind in these types of cases. A bleeding bone bed, large and deep defects, mechanical axis deformities, lesions on the opposing side of the defect, patient age (biologics tend to better in patients less than 40 years old) or difficulty complying with a non- and partial-weight bearing rehabilitation protocol, can all have a negative effect on the outcome of biologic treatments. If these concerns exist, then alternative treatments should be considered.

All biologic treatments require patients to comply with a rehab protocol that consists of a period of non-weight bearing on the operated limb, then partial-weight bearing for several more weeks, usually with the use of crutches, and then extensive physio and rehab that could take from 12 to 18 months to complete before returning to sports. If the patient needs to return to work or has physical responsibilities that require them to be active soon after the procedure, biologics may not be the ideal option. This is where a correctional osteotomy to realign the joint or the newer focal implants should be considered as an osteotomy may provide a solution that allows a quicker recovery.

Osteotomy

An osteotomy in this situation consists of cutting the bone and then either opening up a wedge or removing a wedge of bone to straighten the leg. A plate is put in for temporary fixation to allow the bone to heal. The idea is to prop up one side or drop down the other side of the joint so that the limb is realigned to a more neutral axis. This is relevant when the jjoint cartilage destruction is affection just the one half of the knee, while the other half is still in good condition, and the realignment is designed to take the stress off the damaged half.

Osteotomy has the benefit of the surgery being outside of the joint cavity itself, and the joint surfaces, ligaments and menisci are not actually interefered with. The rehab protocol is generally quicker than other biologic treatments, and new modern plate designs allow earlier weight bearing.

Focal implant

Another option is a focal implant. These are small metal implants designed to replace a focal defect in the joint cartilage without doing anything to the opposing side. Focal implants allow immediate weightbearing, a shorter rehab period and therefore a much quicker return to activity and work. In the image on the right (a model bone) the implant has been placed on the rounded condyle of the femur.

The technique is similar to the resurfacing procedures above, and the implant and its stem are fixed in place with or without cement. Again, there is no major bone block taken and no removal of ligaments or menisci. This may 'buy time' before a knee replacement is needed or may avoid it altogether.

Would a lesser intervention have sufficed?

Early cartilage damage may be present in the absence of associated pain, but over time the underlying bone may become compromised and irritated, and the 'synovial' lining of the joint cavity may become inflamed. This synovial lining may secrete enzyme-rich fluid into the joint, and the initially localised problem may take on a destructive capability of its own. Intervening at the earlier stage - even before pain becomes a significant issue - may heal the defect, and prevent the bone and synovial irritation. Evaluating and improving joint stability and alignment may also limit stress on the vulnerable area.

Evaluating over time integrity of the joint cartilage

A CT or MRI scan gives a good idea of the depth and integrity of the joint cartilage. If this is followed over a period of time from the initial damage, then the surgeon can assess the speed of progression and necessity to intervene.

Assessing stability of ligaments and menisci

A good history and examination will highlight any issue with the cruciate and collateral ligaments and the menisci. X-rays may show any narrowing of the joint space due to meniscus problems and cartilage loss and those will further add to the overall assessment.

Evaluating patellar alignment

Cartilage damage may be limited to the back of the patella (kneecap) and the groove in which it lies. A good history and examination, as well as X-rays and a well-documented series of measurements will give a good idea about the situation in the kneecap. Kneecap malalignment is fairly common and poor tracking can contribute to early wear of the cartilage.

Assessing and recording limb alignment, and where appropriate correcting it

Long leg standing X-rays with computerised measurements will highlight any alignment issue that may be aggravating the forces going through damaged joint cartilage. Realigning the mechanical axis in the knee can help balance the loads in the joint and slow or eliminate further progression.

Supporting some healing of the defect by encouraging local bone marrow biologics

In the early stages, healing of the damaged area may be encouraged with PRP (platelet rich plasma) injections that have various growth factors in them. Stem cell injections from the patients own marrow or amniotic sources may offer an opportunity to heal and provide anti-inflammatory effects and pain relief.

If surgery is indicated in the early stages, then nanofracture and microfracture – where a pick or needle is pushed through the bone plate under the cartilage layer to allow stem cells to enter the damaged area from the bone marrow - may allow some healing over of the cartilage defect.

Where applicable filling the area with cartilage cells, bone and cartilage grafts or scaffolds

ACT, MACI or NAMIC – combining marrow elements, PRP and scaffolds, usually collagen, in a one-step procedure or the multiplication of chondrocytes (cartilage cells) in a laboratory for re-implantation into the arthritic area in a two-stage procedure.

MATT - microfragmented adipose tissue transplantation

OATS and Mosaicplasty - the transplantation of small dowels of bone and cartilage, usually taken from a healthy part of the knee, and then transplanted into the damaged area.

Further reading

https://www.orthocarolina.com/assets/user/upload/files/Articular%20Carti...

http://davidsonorthopedics.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/Presentations-...