Physiotherapist, Lesley Hall, explains why an ACL injury is significant.

First published in 2008, and reviewed August 2023 by Dr Sheila Strover (Clinical Editor)

First published in 2008, and reviewed August 2023 by Dr Sheila Strover (Clinical Editor)

Cruciate Ligament Rehabilitation - course

Mrs Lesley Hall is a physiotherapist with a massive experience in knee rehabilitation.

-

So you've torn your ACL?

- The early management of ACL tears

- Exercises in the early stage after ACL injury

- Clinical assessment of ACL tears

- Torn ACL - should I have an operation?

- General principles of ACL rehabilitation

- Progressive rehab while deciding on surgery (I)

- Progressive rehab while deciding on surgery (II)

- Cruciate ligament rehabilitation - Rehab after surgery

Welcome to my short course about anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) tears. My name is Lesley Hall and I have been a physiotherapist in the UK for over 25 years.

I was privileged to be one of the original physios (PTs) at the Droitwich Knee Clinic when it was founded in 1988, and have worked almost exclusively with knee and lower limb problems since this time.

Over the years I have developed a special interest in ACL injuries and their management, having followed the various developments in this area from artificial ligaments to natural grafts, and the changing concepts for rehabilitation. I am also involved in the educational role of the Knee Foundation, both planning and lecturing on courses for doctors, nurses and physios. I have been invited to speak at international conferences on both ACL rehabilitation and Isokinetics. I have recently completed a Masters degree and have an ongoing study looking at ligament laxity following ACL reconstruction. In completing a literature review for this study I realised how much conflicting evidence there is in this area. General advice available to the public is also very confusing, making it difficult for anyone with an injury to determine the correct course of action.

I am assuming that anyone going through this tutorial has already been given the diagnosis of a torn ACL. My first aim is to help you build a basic understanding of the function of the ACL and the consequent implications of injury. I will then go on to give an overview of the various management options available and the pros and cons of each. Hopefully you will then have a clearer understanding and be able to make a more informed choice regarding the most appropriate course of action for you.

You may have injured your knee while playing a contact sport - a tackle, an awkward landing or a sudden twist - it could have been an individual sport such as tennis or skiing, or you may have had an accident in everyday life. Whatever the cause, the subsequent management is not always clearcut, often leading to confusion for the injured person. Understanding the function of the ligament will help you to follow the logic behind treatment principles.

What does the ACL do?

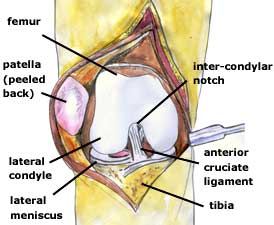

The knee joint is a complex structure designed to allow normal function whilst withstanding the huge stresses we put through it during everyday activities and sport. The main weight bearing part of the joint is formed between the two rounded 'condyles' on the end of the femur (the thigh bone) and the flatter top surface of the tibia (the shin bone).

The space between the condyles of the femur is called the 'intercondylar notch' - this provides the surface attachments for two of the main ligaments in the knee. The notch extends forwards forming a groove at the front of the bone (the trochlea); the kneecap (patella) is situated at the front of the knee and is shaped to sit and glide in the trochlea during movement of the joint.

The knee could be thought of as a 'hinge joint' - this means that movement is restricted to one plane - ie. bending and straightening in a forward / backward direction. This however, is rather too simplistic - the knee is a complex structure where some rotation also occurs, thus allowing a locking and unlocking mechanism to take place.

Ligaments of the knee

There are four major ligaments in the knee - the collateral ligaments which are outside the joint on either side, and the cruciate ligaments which are in the centre of the joint and form a cross, hence the name.

Ligaments attach bone to bone and basically hold the joint together. There is a small amount of give in a ligament but it is not essentially an elastic structure, its function is to limit unwanted movement in the joint. The bony configuration of the knee lacks stability - this is provided primarily by the ligaments and they in turn are protected by strong muscle control.

The ACL (anterior cruciate ligament) is in the middle of the joint and passes from the centre front of the tibia, upwards and backwards to attach to the outer side of the intercondylar notch. It is responsible for controlling forward glide of the tibia in relation to the femur, this movement is known as 'anterior tibial translation'. The ACL also works in conjunction with the other ligaments (the posterior cruciate ligament and the collateral ligaments) to restrict rotation (or twisting) of the knee.

How does injury occur?

Firstly, let's point out that the ACL is a very strong structure. It takes 1700N of force to break the ACL and usually, during everyday activity, the maximum force we put through the ligament is approximately 450N. Obviously when we start to take part in certain sports or if we have an accident then those force levels can increase significantly.

A large percentage of ACL injuries occur whilst playing contact sports such as football and rugby. However, surprisingly, most happen in a non-contact situation. Commonly there is sudden deceleration followed a change of direction (a footballer sprints to the ball, slows quickly and twists as he kicks the ball in another direction to the one he was travelling).

Twisting injuries are also common in skiing and often occur while stationary or moving relatively slowly - rupture of the ACL can occur particularly if bindings fail to release. The effect of the ski is to increase the lever arm of the lower leg thus magnifying stress through the knee. Modern ski boots add to this by holding the ankle rigid (reducing the likelihood of ankle injury) - this has been at the price of additional stress at the knee.

Some injuries occur as the foot strikes the ground with the knee almost fully straight - impact from behind can cause increased strain. This situation can occur both during sport or in everyday life.

Finally, sports which involve high impact landing can increase risk of injury. Any fault in landing technique, whether by personal failure or disruption by another player, can lead to high twisting forces passing throught the joint.

There is a theory that some injuries occur in people who have exceptionally strong quadriceps muscles (on the front of the thigh) in relation to their hamstring muscles (on the back of the thigh). Injury occurs when the quads work suddenly in an 'eccentric' mode - that is, in a deceleratory function or against gravity, and the hamstring muscle fails to counteract the anterior displacement of the tibia.

BACK TO INTRODUCTION: Cruciate ligament rehabilitation

NEXT PART: The early management of ACL tears