Professor Wilson highlights the Apley system for examination of the injured knee.

First published by knee surgeon Adrian Wilson in 2010, and reviewed August 2023 by Dr Sheila Strover (Clinical Editor)

First published by knee surgeon Adrian Wilson in 2010, and reviewed August 2023 by Dr Sheila Strover (Clinical Editor)

Examining the acutely injured swollen knee

Graham Apley was an extremely well thought of and eminent orthopaedic surgeon who was famous for his teaching of clinical examination in orthopaedics, and in fact he set up a course at the Rowley-Bristow Hospital in Chertsey.

He had a very simple way of breaking down orthopaedic examination into LOOK, FEEL, MOVE – so we inspect or look first, then we palpate, then we move the joint.

He had a very simple way of breaking down orthopaedic examination into LOOK, FEEL, MOVE – so we inspect or look first, then we palpate, then we move the joint.

When your knee is acutely swollen and you come into A&E, it is difficult to assess the knee and even senior trainees are frightened to examine the swollen knee because the patients are in pain. It makes it more difficult but it is certainly not impossible – if one takes a history and you put that together with a limited examination on the day of injury even if the knee is extremely swollen it is always the case that you can work out what’s torn and where it is torn and how badly it is damaged.

Looking

When we inspect the knee we are looking for any obvious skin damage, and breaks in the skin, any obvious bony deformity, and any swelling around the knee, and we grade the swelling as mild, moderate or severe – and being simple souls we orthopaedic surgeons often break it down into grades I, II or III which basically equates to ‘swollen a bit, moderately or a lot’!

Feeling

Here we are trying to localise where the pain is, so we palpate around the knee, feeling the joint lines and feeling the origins and insertions of the ligaments, and where structures are torn the patient will experience more discomfort on palpation. By knowing the anatomy and knowing where these ligaments take their origin and where they end up inserting, it’s easy to determine where the injury has occurred. If you damage your extensor mechanism, which are the three structures at the front of the knee that allow you to straighten your leg - namely the quadriceps tendon, the patella and the patellar tendon – if one of these structures is damaged, either the tendon torn or the patella fractured, it will be impossible to lift the leg straight up off the bed, so this is one of the first things that we do. We then, as mentioned above, feel around the joint line and feel around the ligaments. Very commonly patients come in with pain and swelling on the inner aspect of their knee. If one were to feel around the knobbly bit on the inside of the knee, which is called the medial femoral condyle and is the origin of the medial collateral ligament, and the patient were to experience discomfort as is often the case, one can then determine that this patient has injured their collateral ligament. Likewise if one palpates down the length of the ligament and onto its insertion, you can actually determine where the ligament has been injured.

Moving

Locked knee

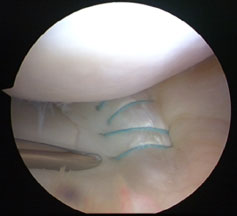

The approach is that if someone is in pain and the knee is very swollen then it is a limited examination, and one has to be realistic. With the knee out fully straight we call that zero degrees, and that is the starting point. And then we see how far the patient can bend the knee (flex) and we compare this with the normal side. The most one can normally flex the knee is about 140 degrees. The patient frequently holds the knee in a slightly bent position and may have a very much reduced range of movement, and will often struggle to get the knee out fully straight. If it is impossible to get the knee out fully straight as part of the examination and the knee is truly ‘locked’ as we call it, then that quite commonly is due to one of the menisci (usually the medial) tearing and flipping into the middle of the knee, and that is called a ‘bucket handle tear’. A bucket handle tear is relatively common, and the story is usually that of a young sportsman who has an injury, the knee swells up immediately or perhaps several hours later, they come into A&E and they cannot fully straighten their leg.

A meniscal tear is a relatively important diagnosis to make, and more importantly it is a relatively important problem to sort out acutely (a) because it is really painful and (b) because the best time to fix the meniscus is in that early period just after the knee has been injured (within six weeks). If someone comes in with a locked knee though, you don’t leave them stewing for six weeks - they should be admitted straight away. You can get an MRI – there is no harm in getting additional information – but the knee needs to be unlocked and generally speaking that means an arthroscopy, the flipped meniscus is reduced and it is stitched back into postion if you have the skills to do that. We routinely now carry out meniscal repair in that sort of situation.

In terms of bending the knee, often patients cannot bend it after injury much more than a right angle (90 degrees) but once you have got it up to 90 degrees it then allows you to begin to examine the ligaments in a systematic way.

Ligament tears

The four ligaments that we are primarily interested in are the two cruciate ligaments (anterior and posterior cruciate ligaments) and the two collateral ligaments (medial and lateral collateral ligaments). There are of course other bits that we are interested in but those are the four main ligaments that we examine. We also make sure that the patient hasn’t damaged the ‘extensor apparatus’ (the tendon that goes from the quadriceps muscle down to the patella, the patella itself, and the patellar tendon). This is very simple – if the patient can fully straighten the leg and lift it up in the air the extensor apparatus is basically working.

Anterior cruciate ligament - To take the anterior cruciate ligament first, if the patient can flex to 90 degrees we look for increased movement of the shinbone forwards from the thighbone, and that is easy to do. The patient’s foot is steadied by gently sitting on their toes and then the tibia is drawn forward on the femur. If it comes too far forward, the patient has almost certainly ruptured the anterior cruciate ligament.

Now with the knee at 90 degrees we then feel to see if the tibia has dropped too far back on the femur – is there what we call a ‘step off’ on the medial side of the knee? In other words when we feel the medial side of the knee, if we run a thumb down the end of the thighbone and onto the shinbone, the shinbone should be in front of the thighbone – we have this step forward. If the posterior cruciate ligament is ruptured and the tibia (shin) is dropped backwards then you can feel that with your thumb. So you press on the femur with the thumb, and come down and are expecting to come forward on the tibia but instead you go backwards – the step off – which indicates that the posterior cruciate is ruptured.

Posterior cruciate ligament - To assess the situation in more detail we then push the tibia backwards to see if it goes too far in the posterior (backward) direction, and if it does then this confirms the rupture of the posterior cruciate ligament. We grade that ‘posterior drawer’ according to how far back you can actually push the tibia - If you can only push it a bit, then it is a grade I injury, if you can push the tibia up to the level of the femur but not beyond, then it is a grade II injury, and if it goes beyond the level of the femur it is a grade III injury where it won’t have an ‘end point’, ie there won’t be any resistance there at all, just this soft feeling as you are pushing backwards.

Now we have partly examined the anterior cruciate ligament and we have all the information we need about the posterior cruciate ligament, and now we put the leg out straight and take hold of the big toe and lift the leg up by it to see if there is excessive bowing (recurvatum) at the back of the knee, in other words the knee extends too much and appears to bend backwards. This excessive extension or hyper-extension or recurvatum as we call it indicates that the structures at the back of the knee have been stretched and injured. It may not be possible to do this when the knee is swollen with blood and painful, but if the posterior cruciate ligament is ruptured actually the bleeding may have escaped from the knee as a posterior cruciate ligament rupture is ‘extracapsular’ (outside the knee cavity) and the blood may run down within the calf. In a posterior cruciate ligament rupture the knee may be a bit swollen but not nearly as swollen as when the anterior cruciate ligament is ruptured where you have quite tense bleeding within the knee and that is very very painful. So there is much more pain for the anterior cruciate ligament, and much less swelling and much less pain for a posterior cruciate ligament rupture.

We then do what is called the Lachman test and that in the acute situation is done best by resting the knee slightly bent over the examiner’s own knee. So the examiner puts his own knee up onto the examination couch and slides it beneath the patient’s painful swollen knee – and often that is the most comfortable position for the patient to be in so they usually are quite relaxed like that and will flex their knee over the examiner’s knee to allow him to do the Lachman test.

The femur is held in position and the tibia is drawn forward, and if there is excessive movement it suggests that the anterior cruciate ligament is ruptured. In the acute situation it is often not possible to do the so-called ‘pathognomonic’ (or most sensitive) test for cruciate rupture which is the pivot shift test, which is a special test for the anterior cruciate ligament. Basically the anterior cruciate ligament is like a fulcrum in the middle of the knee – so you have this structure that (if it is there) is the central rotation point of the knee right in the middle of the knee. If the ligament is not there then the centre of rotation of the knee changes, and by doing this test the tibia initially shifts slightly out of position then as you flex the knee up and apply the correct amount of internal rotation and force on the side of the knee the tibia pops back in again. That only happens if you have ruptured your anterior cruciate ligament.

We finish off the examination by assessing the collateral ligaments. In the really swollen knee this is almost the most important thing to pick up because in someone who does have a very painful swollen knee it is difficult to assess, and if all the examiner is able to do is a Lachman to say ‘Yes, the ACL is gone” and then examine the collateral ligaments to see if they are intact, you have probably done enough. This is because if you have ruptured your ACL and nothing else, and your knee isn’t locked, it is fine to let the knee settle down for a few weeks. If you have ruptured your collateral ligaments you really need treatment to begin on Day 1 to try and manage that in a conservative fashion . The way the collateral ligaments are assessed is that the leg is put into full extension and a force is applied on either side of the knee to see if the ligament opens up on either the inside of the knee or the outside of the knee.

Medial collateral ligament - If you put a valg-ising force, in other words you are trying to bend the shinbone outwards sideways in relation to the femur, to assess the inner medial collateral ligament, if it doesn’t open up at all but the patient is exquisitely tender over the origin or insertion of the medial collateral ligament or along its length, we grade that as a grade I medial collateral ligament injury. That doesn’t really require anything other than painkillers, rest, physiotherapy, anti-inflammatories – and usually it will settle down very quickly.

If the knee is fully stable in extension but you apply that force with the knee slightly bent to 30 degrees and it opens up slightly more than it should do, then we grade that as a grade II injury – that too will settle quickly and although it is often helped with bracing it does not require much more than for a grade I – painkillers, physiotherapy and so on.

If, however, the knee either in full extension opens up or slightly bent it opens up and it does not have a firm end to that (it just keeps going) we grade that as a grade III injury – and that is the one that we really want to pick up in the acute setting, because the inner ligament of the knee heals extremely well with conservative management. For years the treatment has been that the patient has been immobilised in plaster for four weeks with the leg straight - and that is the way it was done when I was training. Over the last ten years or so, we have learned that that is not actually the best way to manage a significantly torn medial collateral ligament. In fact if you want it to heal up properly you have to brace the knee with the knee bent – in this position it heals but with the ligament slightly short, so as you take the patient’s knee back out straight again over the course of six weeks they have the correct tension in the medial collateral ligament. If you put them in plaster or put them in a brace out straight - which unfortunately is still done in this country in lots of institutions because that is the way it used to be done since records began, and people haven’t moved on – it will heal, but it will heal long.

So it is really important with the medial collateral ligament to brace it, and brace it quite aggressively if it has been torn badly. What we tend to do is we have a range of movement from 30-60 degrees for two weeks, 20-90 degrees for the next two weeks, 10-full flexion for the next two weeks and finally the patient comes out of their brace usually at about six weeks – and nine times out of ten the medial collateral ligament will have healed and you will require no surgery. If you don’t pick that up and the patient is allowed to go on to have a long medial collateral ligament then you are getting into reasonably complicated surgical territory – reconstruction of the MCL isn’t an operation that is done too frequently, there aren’t too many surgeons that can do it and it is something that one just needs to avoid. Often, as I mentioned before, the knee may be injured in several parts and you could make a quite complicated problem much more straightforward to fix if the surgeon can sort out the MCL and then all that you are left with is a meniscus and an ACL to sort out.

Lateral collateral ligament - So that is the medial collateral ligament. If you apply a var-ising force to the knee (opposite to the way we assessed the medial collateral ligament) this will allow the integrity of the lateral collateral ligament to be assessed. In the same way as with the medial side you do it with the leg straight or slightly bent, you can work out whether the lateral side of the knee has been injured or not. We grade it in the same way – in grade I the knee is stable out straight and bent, grade II the knee is stable straight but it opens up too much on the outer side when the knee is bent slightly and force is applied, and grade II it is unstable both straight and slightly bent. Now again that is really important to pick up because if you have got a grade III lateral injury that won’t heal by itself and those need to be operated on acutely. If you get to them within the first few weeks it is relatively straightforward to put the jigsaw-puzzle together again - do an exploration and find the relevant parts of the lateral complex that are ruptured and suture (sew) them back into their normal anatomical position. It is difficult surgery but very rewarding surgery and you can only really do it in the first couple of weeks. After that time the tissues start to be very difficult to work with. Unfortunately a lot of people who have that injury don’t get picked up and they go onto have chronic ligament instability or a situation which is unreparable and there you are into the realms of reconstruction as opposed to repair.

Haemarthrosis - If the patient is in lots of pain it is sometimes for first-aid purposes worth putting a needle into the joint, aspirating the blood and filling the knee with local anaesthetic. That will make the patient feel much more comfortable. It is not something that generally speaking needs to be done – in most people that rupture ligaments the pain will be manageable by immobilisation in a brace, appropriate analgesia, rest and elevation of the leg – it is not a good idea to go sticking needles into the knee unless you have to because wherever you put a needle there is a risk of introducing infection. It’s not something that would be done routinely.

Examining the joints above and below the knee

Beside the knee, the examiner also needs to assess the hip, examine the femur, tibia and ankle.