In certain cases it may be appropriate not to operate on anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) tears, but most surgeons would accept that if the patient is symptomatic and the joint unstable then surgery is critical to prevent further damage and long term problems.

The goals of ACL reconstruction are to stabilise the knee joint in as normal a way as possible, and thus prevent early arthritis joint damage. Despite a century of research it still is not possible to fully restore normal knee function. However, there has been constant improvement understanding over the last 30 years, which in turn has yielded significant improvements in the clinical outcomes.

Evolution of understanding and surgical technique

Turn of the century - 1970

At the beginning of the 20th century, efforts at stabilising the joint after a tear of the ACL focused upon 'open' surgery and repair rather than reconstruction of the torn ends.

The first recorded reconstruction was in 1912, using fibrous tissue taken from the outer side of the patient's thigh. This was soon followed by early attempts to reconstitute the anatomy by pulling the graft out into bony tunnels.

It was a problem at that time that there were no standardised tests to assess the integrity of the ACL, but by the 1970s the 'pivot shift test' and the 'Lachman test' had become accepted, and surgeons accepted that it was important to control 'rotatory instability'. Surgeons started to do 'extra-articular' reconstructions, taking harvested tendons around the joint rather than through the centre of the joint, but residual instability and arthritis continued to be a real problem, so attention was re-focused on 'intra-articular' reconstructions.

The 1980s to the end of the millennium

The advent of arthroscopy (keyhole surgery) became important in confirming diagnosis and also as an adjunct to 'open' procedures. A 'gold standard' was accepted of drilling tunnels/sockets via the tibia, producing a reconstruction that stabilised the joint laxity in a front-back direction, but not really offering adequate stability in a rotational direction. This period also saw the introduction of screws to fix the ends of the reconstruction.

Millennium to Current period

Surgeons began to realise that the native ligament was comprised of two bundles which took the strain differently at different flexion angles of the knee, and techniques started to focus on 'double-bundle' methods to try and reproduce the normal anatomy, but this has again moved on back to using a single bundle but improving the positioning of the ligament to be more anatomical, although controversy persisted surrounding the optimal reconstructive technique, with no ACLR technique fully restoring normal anatomy, kinematics and function to the knee.

Another significant step forward was in improvement of understanding of the factors involved in the high incidence of ACL tears in women athletes, and the introduction of specific training programmes to improve this situation.

The current period has focused heavily on fully identifying the anatomy of the 'footprint' of the ACL within the notch of the femur (where the ligament attaches at its upper end), and ligament surgeons took good note of the new work of Claes's team who brought to attention a well-defined ligamentous structure called the anterolateral ligament (ALL), which seemed to be the missing link in understanding residual rotation after ACLR.

There has also been a realisation that the stump of the native ACL is important to preserve, as it contained fibres of 'proprioception' (which gives the joint its position sense) and also blood vessels that enhance biological healing. A stumpt also gives mechanical support to any new graft.

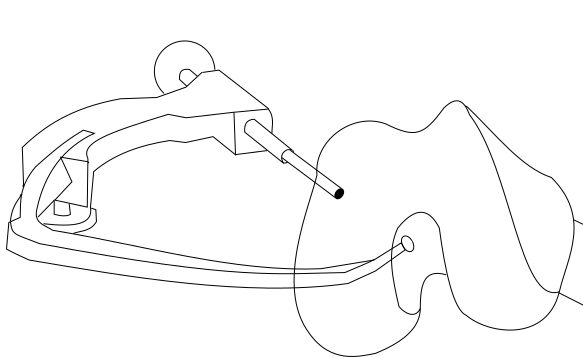

Techniques have changed - leaving behind the old 'gold standard', and adopting an 'all-inside' approach 'trans-lateral' approach that avoids the old non-anatomical graft positioning. The new approach was facilitated by the development of anatomically-contoured instrumentation, flexible reamers, an additional new portal (skin cut for passing instruments), smaller bone tunnels and fluoroscopic imaging.

Modern graft choice

Autografts - where the graft material is harvested from the patient - is preferred in the UK (where this publication comes from) over allograft (from a donor), but discussion continues about whether the graft should be taken from the patellar tendon or the hamstrings. A systematic review comparing these grafts showed no difference in terms of survivorship or functional outcomes, but the trend has swung towards using hamstrings tendon for the graft as it gives less problems at the harvest site, and it is especially indicated when the patient relies on kneeling in their occupation.

Traditionally, both the semitendinosus and gracilis tendons are harvested and doubled over to create a 4-strand ACL graft. Despite this doubling over, it is still not mechanically as strong as a patellar tendon graft, and in the USA is often supplemented with allograft. However, it has been found that the semitendinosus alone can be taken, and tripled or even quadrupled to give a wider and stronger construct as newer techniques can accommodate a shorter graft.

Quadriceps tendon can also be used with less of a harvest site problem than patellar tendon.

In the USA, allograft is popular and often preferred over autograft, as there are no problems with the harvest site.

Modern fixation devices

This is still an area where there is a lot of discussion. The fixation dictaties the mechanical properties of the graft during the critical early healing phase, maintaining graft position and tension until full biological integration of the graft within the socket has occurred.

Metal screws have largely been replaced with bio-degradeable screws. In those grafts where there is a bone block at least at one end - such as patellar tendon and quadriceps tendon grafts - attempts may be made to achieve a 'press-fit'. Other devices and bone are also being used to help add additional strength especially in cases of revision surgery where there are old and widened tunnels. In the hamstrings grafts, the fixation depends upon the technique employed, but a popular fixation in the shorter grafts mentioned above is a 'suspensory' fixation, with the folded graft material suspended at each end enabling the device employed to adjust and tighten the whole construct.

Graft reinforcement and internal bracing

Synthetic material, popular in the 1980s, has fallen out of favour as they tended to leave irritant particulate matter in the joint if they failed. However, a third generation of ultra-high molecular weight polyethylene terephthalate tapes are coming into modern use as an ‘internal brace’ to allow the 'repair' rather than reconstruction of ACL, or more commonly the posterior cruciate ligament (PCL), if surgery is undertaken in the early period following partial or complete rupture. Or in a hamstrings graft if the semitendinosis is flimsy or short it can be reinforced with this kind of tape.

ACLR and the anterolateral ligament

Where there is a marked positive pivot shift test - ie rotatory instability - the very modern approach is to perform a reconstruction of the antrolateral ligament. The senior author in collaboration with Stephen Claes and his team, has devised a minimally invasive anatomic reconstruction with encouraging early clinical results, and no detrimental outcomes although the long-term outcomes are yet to be determined.

The paediatric ACL

Children with torn ACLs provide special challenges to the knee surgeon. It used to be thought that this was a relatively uncommon injury, but increased awareness in children engaging in competitive sports has brought to our attention that children account for 0.5 -3% of all ACL injuries.

Consideration of the growth plate in children is critical when considering the management of a torn ACL as damage to this can result in growth abnormalities. The Tanner staging is useful in predicting risk of growth disturbances [Ed. See this comprehensive overview by Professor Wilson]. Tanner 3 and above have less chance of significant issues due to their reduced growth potential, and newer techniques of acute repair with growth-plate-sparing have removed the stigma of ACLR in the skeletally immature, reducing the risk of secondary injury. Parental donation of allograft also helps to reduce harvest-site problems for the child.

Special drill guide for all-inside approach